Not Them, Sir: The Others

8 Feb 2008

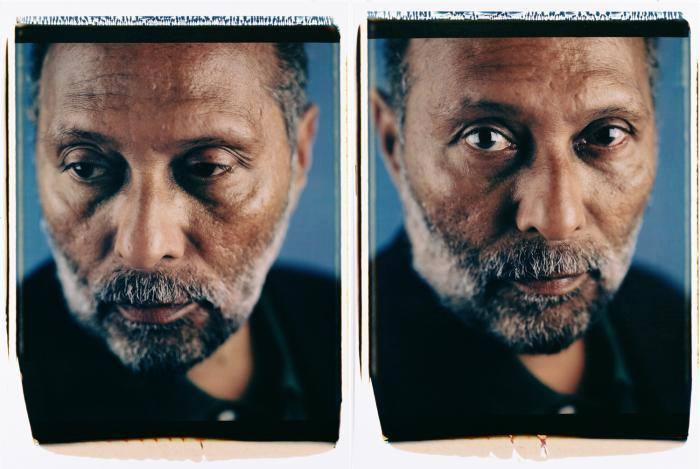

An interview with ECF Princess Margriet Award laureate Stuart Hall by David Cameron

It’s not every day I get to dine with three princesses,’ Stuart Hall says, eyes twinkling. And well they may: after all, it is Karl Marx’s name that gets mentioned more than any other as we chat in a city-centre Brussels hotel – not comfortably, in the lobby, but in two awkward wooden chairs beside the lifts. Yesterday the very non-bourgeois Hall was being feted by European royalty, policymakers, and cultural ideologues, as a laureate of the first-ever Routes Princess Margriet Award for Cultural Diversity. Though not officially a ‘lifetime achievement’ award, the citation made it clear that this was what was meant.

And a distinguished life it is, shaped originally in Jamaica and reshaped in 1950s England. The welcome mat was as bristly then as now – though hostility was less guarded. For ‘no blacks, no dogs, no Irish’ then, read ‘a vigorous debate about immigration’ now. ‘Immigration is only a coded word for race,’ Hall says, surveying the political scene in contemporary Britain with dismay.

A Rhodes scholarship gained Hall admittance into Oxford. He later became a pioneer of cultural studies, latterly with the Open University, which made his a familiar face on late-night TV. His brand of political engagement can be said to have altered history, since his ideas have been credited (discredited, he might himself say) with helping reshape the Labour Party in Britain. New Labour is anathema to him. ‘You cannot even argue with it,’ he says. ‘It uses the same words – “community”, “society” – but emptily, without meaning.’

After decades of cultural theorising, Hall – in his late 70s and coping with kidney failure – has said goodbye to all that, professionally at least, and thrown himself into the visual arts, first as chair of INIVA (Institute of International Visual Arts) and Autograph ABP (Association of Black Photographers), and recently as a driving force behind the new, highly diverse cultural centre in London, Rivington Place. He likes the tangible form of the visual arts, he says, and laughs off the suggestion that there might be any disconnect between this tangible sphere and the abstract one of cultural theory. ‘It’s the same old story in another media,’ he says, asserting that propagandist art holds little appeal for him, a statement he quickly qualifies by saying: ‘No, I’ve no rooted objection to it. For second-generation African-nation artists in the early 80s it was valid. But neo-conceptual art can’t work like that.’

It is Hall’s career-long attempt to make sense of our multicultural societies that has brought him to a Brussels podium at the tail-end of 2008, the European Year of Intercultural Dialogue, to accept an award that celebrates diversity. Yet he confesses to being uncomfortable with the language of diversity: he prefers the term difference. ‘At times a kick is more appropriate than dialogue,’ he says, as if gauging my own susceptibility to simpleminded liberal goodwill and tolerance. ‘Something resists dialogue, and this isn’t to be wished away.’

For Hall, the language of globalisation is just as spurious. ‘What we have is combined uneven development. Though cultures may be interlocked, deep inequalities remain. There is now a different kind of imperial relations, and class structures are in transition. You can now have your working class in the third world.’

He says that it his not his aim to stand up for ‘multiculturalism’ as such, but to consider what policies might bring equality in a multicultural society where differences occupy the same space. The advent of the new, post-9/11 ‘language of terror’ has made it much more difficult to create the conditions needed for honest confrontation, he says. Cultural difference has become much more racialised, and mixed up with this is the return of religion. Though he is not anti-religious, Hall admits to being afraid of religion.

‘Faith, as opposed to reason, puts religion beyond negotiation. Can we talk about the veil? Yes. The open face is at the centre of democracy, and the veil’s use in public office causes difficulty, though I can understand why women are afraid of the male gaze.’

Of course, racism is nothing new. Hall remembers his early days in England when he taught at a school in East London. One day he was on a bus when he encountered white pupils of his who were on their way to Notting Hill to fight black youths. Asked why they hated these youths when there were black kids in their own class, the boys replied: ‘Not them, Sir: the others.’ Hall has no time for present-day politicians who advocate ‘colour blindness’ in human relations. Difference in colour registers, though not necessarily negatively.

At the previous day’s ceremony, Hall was in good form, graciously accepting the Routes Award conferred on him by the European Cultural Foundation while pointedly warning of the dangers facing cultural institutions that stay too close to traditional artistic and political elites: ‘Can they really open, or be made to open, themselves to the radical project of learning to live with difference, to the emerging possibilities of a diverse, pluri-centred cultural world?’

Today, in relaxed mood, he speaks of his delight in life’s incongruities, As the talk drifts to English literature, he recalls how his friend, the Marxist historian from Trinidad and Tobago, C.L.R. James, would re-read the Victorian novel Vanity Fair each year. Surprisingly, Hall began his studies at Oxford doing a PhD on the novelist Henry James, which he abandoned as his interest in cultural issues grew. His eyes brighten as he recounts the plot of James’s novel The American, and too soon it is time to go.