Ivan Krastev in conversation with Philipp Dietachmair – Part 1

19 Jan 2016

A print friendly version of the complete conversation is available for download (PDF)

15 Years in the Neighbourhood Ivan Krastev in conversation with Philipp Dietachmair

We invite you to dive into this fascinating and much needed conversation with one of Europe’s most respected and knowledgeable political scientists. We have divided the interview into five parts and will publish one every week between 19 January and 16 February, to allow a deeper look and time for reflection on the history of the role of culture in the larger European project. We also invite our readers to join the dedicated ‘Another Europe’ Lab on ECF Labs where you can participate to the discussion on issues around these particular themes and download more texts on our work in the EU Neighbourhood as featured in our most recent publication.

In part 1 of our conversation, Ivan Krastev discusses the powerful drive behind the expansion of the European Union and various institutional blind spots he observes when it comes to acknowledging historical and cultural divides. He then focuses on the particular cultural and political conditions of Eastern Europe and Russia where the dissolution of the Soviet Union has led to an identity crisis that was instrumental in growing nationalistic sentiments.

PART 1: Looking Back

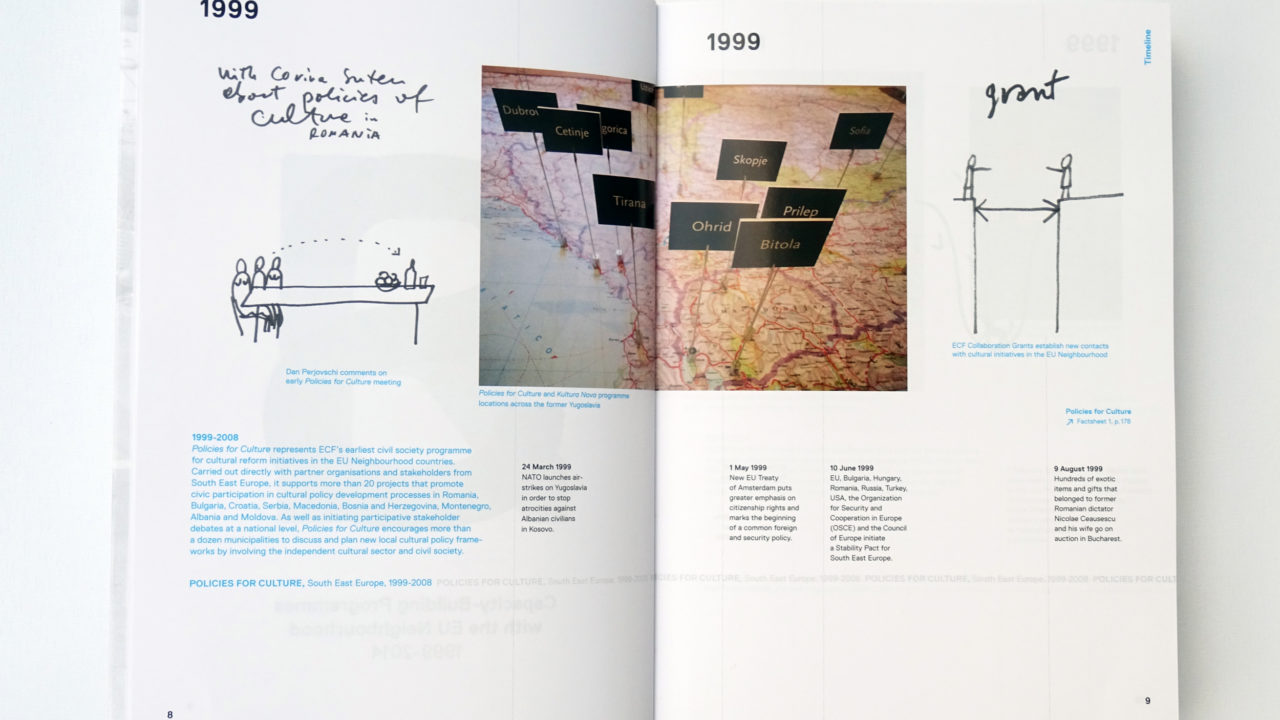

When the European Cultural Foundation started to collaborate with cultural initiatives in the EU Neighbourhood countries in 1999, the wars in Ex-Yugoslavia had just been ended, Eastern enlargement of the EU was only a few years ahead, so was the reopening of membership talks with Turkey and no other EU Delegation worldwide had more employees than the diplomatic representation in Moscow. Civil society in a number of countries along the EU borders seemed to have justified reasons to believe that – with a good deal of persistence – more openness, participation and justice would eventually become achievable in their societies. After 15 years of building capacities with cultural managers who operate in ‘turbulent times’ (to quote the title of one of our seminal handbooks) violent political developments, repressive (or crumbling) state structures and shifting social realities across practically all EU Neighbourhood regions have left many of the civic initiatives which have collaborated with the European Cultural Foundation more fragile and exposed than ever before. Was their assumption – which was very much in line with the European Cultural Foundation’s own vision – that there was a true perspective for an ever more open, democratic and inclusive wider Europe (reaching across the EU and its neighboring regions) too naïve?

The way we saw the world 15 years ago and the way we see it now has changed a lot. We like to talk about 1989 as a revolution, but nowhere in history has there been a revolution without a counter revolutionary moment. We believed that there was only one story and one narrative: the one of an ever expanded European Union where the institutions, values and practices were going to spread. I believe that we should look back because many of the things that are surprising us now probably had been under the surface and we didn’t manage to see them. People –especially in Western Europe, try to think of the last 25 years as a particularly uneventful time. But say you come from the moon and try to look at what happened in Europe in the last 25 years, you’re going to be surprised! Almost two dozen new states have emerged, and on that level, Europe in the last 25 years can be compared only to Africa in the 1960s.

Instead of looking at one big project, the enlargement of the EU, it would be better to look at four different projects – all four of them in crisis now: One was of course the transformation in the enlargement of the EU, the biggest project because it was a visionary one. It kept a normative aspect and although people didn’t know when the Balkans, Turkey or Ukraine were going to be part of the European Union, they knew that one day they’ll be there. You ask if we’ve been naïve. Yes, we have been. But naiveté can also be part of your strengths. It was exactly this naiveté that allowed people to achieve more than if they’ve had been realistic about what was going on.

However, there have been three other projects running in Europe at the same time: one comprises the problem of the imaginary of Post-Imperial Russia. Never in its history had Russia been a non-empire. It was therefore not easy for the Russian society and leadership to find their place in the world. Whereas for us, the end of communism was perceived as a win-win game. Not many Russians were nostalgic for communism especially in the younger generations, but it was very difficult for us to understand that what the Russians were nostalgic for was the Soviet Union. For them, the end of communism did not mean that the Soviet Union should disintegrate towards this huge crisis of identity. Our failure to look closely into the political or social, but also the very deep identity crisis the Russian society was going through, prevented us from seeing the seeds of this Russia we see today –which cannot be explained simply by the policies of President Putin.

Then new states have emerged in the Post-Yugoslavian and Post-Soviet space, many of which had only their names and borders on the day of their creation. How to build a state in Europe where some of the normal mechanisms of state building –based on suppressing the minorities and coming with a strong nationalistic propaganda, are not tolerated anymore? We didn’t ask ourselves that question, it was so obvious that it was part of history that we didn’t believe something can come after this. Then you have Turkey which also went through a very important transformation: we see the images of Post-Kemalist Turkey which was on one level much more open and democratic but on another level was becoming less Western because of the rise of political Islam.

So you have all these four projects which have been part of the European space. The problem was obvious: are these projects going to support each other or are they going to disturb each other? We have seen in the last several years how this process created clashes, to what extent for example, the failure of the Ukrainian nation state under Yanukovych created also this major crisis in the Russian-European relations? To what extent a new identity that Putin built for Russia basically ended up in the aggressive isolationism that confronted Russia not only with Europe but many other parts of the world? As for the European Union, all this crisis now on its borders created a situation in which certain fragmentation forces can be seen within Europe.

And here comes the problem of culture. In this visionary idea of an ever expanding European Union, culture was very much reduced to the idea of being part of Europe’s soft power. But Europeans have been very much preoccupied with established institutions. All was very much about exporting institutional design, and the idea was that institutions were going to create their own culture, which I believe we have failed to achieve. Although there was a lot of support for certain cultural initiatives, and energy in a new generation that was being shaped, culture was not used as much as it could have been as a source of knowledge about society. Many parts of the problems that we face today can be read in the books, seen in the theatre performances and in the films of this past period. It was always there.

As part of the European project, we have been strongly pushing for creating a very important European, much more cosmopolitan cultural elite and supporting their practices. For example, when they worked on performances that can touch the nerves of audiences not only in Belgrade but also in Zagreb, in Amsterdam, in Berlin… . At the same time, what emerged was a much stronger divorce between this more cosmopolitan, mobile, urban part of society, and the other parts of society which basically felt as losers, not only in socio-economic terms, but they also started to have a huge fear about their identity and their place in the world. We’ve ended up with a situation which is quite different to 15 years ago when it comes to even fundamental questions: if there was one thing that nobody was going to put under question back then, it was the open borders.

Would you say that we focused too much on the young generations and urban cosmopolitan elites who were clearly interested inreaching out? Did we not do enough with groups outside urban areas?

Yes, that’s true. According to us, such groups were less creative, they were less interesting and they were less connected to Europe. We have been very much focusing on this European-minded culture that was produced in places where, in my view it was logical to go. Because these were also the people that were most interested in cooperation, and every cooperation has demands…

We continue our conversation next week with Part 2, which will focus on the future role of culture in bridging the gap between the increasingly polarized factions of Europe, where Krastev argues for the necessity to embrace the populist as well as the elitist discourses in order to constructively, and truly, include all parties, from the cosmopolitan elite to the newly emerging conception of majority that is being galvanized around conservatism through a fear of being persecuted.