Who is we? Or: The revolution of fraternity. An exchange with Bas Mesters.

4 Dec 2018

In 2017, the angry citizen was supposed to topple the political establishment at the elections in the Netherlands, France, Great Britain and Germany. Europe was supposed to erupt. Until now it never happened. Dutch journalist Bas Mesters set out to investigate and found the seeds of a revolution of fraternity. In his series of essays for Dutch weekly De Groene Mesters traveled to France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy and Poland with more countries due. Mesters talks to changemakers who not only dare dream of new democracies but live them, he discusses with thinkers and policymakers and discovers an unsung revolution of fraternity happening across the continent. We discussed his project with him and share excerpts of his essays.

Bas, what got you started?

“Newspaper commentaries along the lines of: Europe is a volcano. Overheated poisonous streams of lava are boiling beneath the surface; 2017 would become the year of the eruption of fragmentation. Books with titles such as The End of Europe or After Europe cast their shadows ahead. Following the Brexit and Donald Trump, the if-then-logic of the media predicted in January that Geert Wilders would destabilise the Netherlands, Marine Le Pen France and Frauke Perty Germany. Europe would collapse under the pressure of immigration, globalization, digitization, the hiatus between world citizens and locals, between immigrants and natives, between young and old, city folk and provincials, knowledge workers and makers, state and people, elite and mass.

At the time, I was wondering: what if the volcano doesn’t erupt? Why wouldn’t that happen? In order to prepare for this unlikely scenario, according to the media, I decided to seek out the geysers, the breathing vents of the volcano. Places where the pressure may be alleviated and where perhaps fertile grounds might emerge.” [The song of the kolibri]

What do those fertile grounds look like?

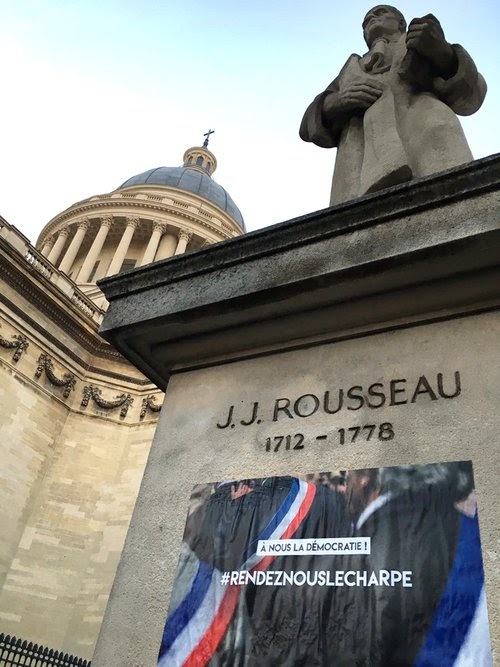

Contrary to doom-thinkers I did not believe the two widely felt frustrations – a growing inequality and a sense of not being recognized – would only become public at the ballot boxes, because people want to act, need to do things together, want to feel close to one another. All over Europe we have seen new bonds emerge between self-organizing citizens. It was during my visit to Paris I found out what I wanted to explore. I met community organizer Hadama Traoré and philosopher Mathieu Niango, who both collaborate in one of those bonds.

“Following the lines of thought of the French Revolution with Rosanvallon one could say that the equality revolution of the nineteenth century, that ended up bringing about the welfare state, was followed by a liberty revolution in the West. The liberty revolution, which for all intents and purposes began with the invasion of Normandy by the allied troops, gave us the freedom to think for ourselves and be heard without the fear of oppression and violence. That newly found liberty instigated experiments, fantasy, creation, flower power, a lust for travel, the fall of the Wall, an urge to discover, a development fever. Starting in the eighties, the market-driven liberty revolution culminated in hypercapitalism, speculation, bubbles and the financial crash of 2008, and it will end up in the impending climate stroke if we don’t do something about it.

All of this has caused a new crisis of equality. Equality will have to be restored once again. However, now that individualisation and privatisation are a fact, and the market is controlling the flow of capital like never before, the state is virtually incapable of organising it. The citizen, the community needs to be involved, says Pierre Rosanvallon. This isn’t necessarily about immediate realisation of economic equality, but rather what he calls realising a new relationship of equality, enabling groups to rekindle their discussion. A brotherhood relationship, as Hadama had called it. Perhaps a revolution of fraternity?” [The song of the kolibri]

Doesn’t fraternity ring an alarmist bell?

Yes, there are at least two dangerous sides to the notion of fraternity. It is gendered. And it easily evolves into an excluding principle, into what I call the brown-shirt brotherhoods. I like to oppose these with what I call the rainbow coalitions. Unfortunately the first ones dominate headlines, whereas the latter are building our future, far away from the media attention. The goal of my European travels is to shed some light on these positive forces.

“I met people who were advancing brotherhood, although they often preferred not to call it by that name. Such as Kazim Erdogan, a psychologist nicknamed ‘the Sultan of Neukölln’ who for years has been helping Turkish fathers connect with each other and with German society. He preferred to use the term ‘good and honest communication’. I suddenly realized that the word ‘communication’ is derived from commune: communality.” [We are way ahead of the city].

“Maria tries to connect them by taking action. It costs her and her daughter and her daughter’s girlfriend a lot of energy, and they have to survive on a few hundred euro a month from summer jobs. Yet they want nothing more than to collect books, give them away, and talk about them. “It gives lonely people an identity and a sense of belonging,” says daughter Weronika. Maria’s library is a focus of resistance in this Warsaw district, building togetherness regardless of colour and origin.

Poland has been a much less friendly place since Law and Justice took over. The party deliberately creates conflicts, Maria says. “It polarizes people against Europe, against foreigners.” It’s all about divide and conquer, and turning a blind eye when people do things in public that they’d never have dared before, like declaring that gay people should be sent to the gas chambers. “The new government promises you a star in the sky. And if you don’t get it they say sorry, we couldn’t give it to you, someone stole the ladder.” [The dream is dead]

Mesters says he encounters examples of this instrumental polarization time and again. Many of the revolutionaries of fraternity address this polarization. Yet, lessons in political framing have taught us that deframing political messages doesn’t work if you name the frame, on the contrary, people will remember the frame even better. To change the story one needs to redirect attention. To do a great job in storytelling. As artists can do.

“You are modern society’s garbage, and are treated as such. Nobody wants you anymore. Let’s build a rocket together and go to the moon. We’ll make a nice game of it and film it.” He called it Space Metropoliz. His idea is that there are more and more “disposable lives”, as the philosopher Zygmunt Bauman described them. Migrants, Roma, the unemployed were all rejects. “So instead of awaiting their fate in the garbage dump, I proposed that we go to the moon together.” [Hell is loneliness]

In Mesters’ words the revolution of fraternity can teach us more than reframing current politics: “It teaches us how to deal with limits, personal as much as shared ones. To act together one needs to know the limits of the partner. It teaches us modesty in the face of our personal ambitions. And that could be healthy in times when we are told everything is possible. We need to learn dealing with things not becoming true in order to make changes.”

“We live in an era of transition from certainties to uncertainties,” says Italian Christian Iaione over lunch. “The great theories and ideas that believe in the market, and that the state sees as the organising principle, no longer hold as much sway as they used to.” Iaione is investigating how the commons, which in the past centuries were highly valued, particularly by fishermen at sea and farmers in the countryside, can also be used in the big city. How should local government deal with these bottom-up forms of fraternity, and what makes such a project succeed or fail?

What Iaione does in Centocelle is to take students from an elite university to a poor neighbourhood to serve the needs of that community, not in pursuit of an ideology or to help people, but simply to work together. “It’s not about participation or talking, it’s about doing things. We’re interested in creating work at the end of the trajectory, an economic reality, joint ventures that can offer a counterforce to the market and the government and increase the economic diversity of the city.” [Hell is loneliness]

This ‘doing things’ is also characterizing Bas Mesters himself. What started as an idea when reading newspapers in early 2017 evolved into this series of essays in a Dutch weekly, but also grew into a series of public events in The Hague. And the series is not ending yet. Bas admits being surprised at the width and depth of the revolution of fraternity: “I never thought this series would last so long. So many people are active in new established networks, as they want to feel ownership over their societies again. They want to live, act, work together. The stubbornness that drives many of this people, is the same stubbornness that got me into journalism. The stubbornness to not accept the world as others tell it to be.” Again, his own ideas seem well reflected in a quote.

“For Sztarbowski and Łysak, the theatre is a laboratory for the development of alternatives. Last year, they wrote the words Freedom, Equality, and Imagination on the front of the theatre. “To us, fraternity above all means imagination. Imagining together how things can be improved.” And the key word in this respect is not strength or power, but care and compassion. “I think the new revolution is one for women in particular. The twenty-first century will be the era of sisterhood.” [The dream is dead]