ECHO mobile library—Mobile cultural exchanges

28 Feb 2021

In the Libraries for Europe programme, the European Cultural Foundation supports a network of European public libraries and the Amsterdam public library OBA to develop European programming and organise encounters between European inhabitants in local, regional and international ways. One of the projects we fund from this programme is ECHO. A mobile library based in Athens, Greece, that aims to nurture a space of learning and creativity and serve as a place to cultivate the mind of migrants and refugees. ECHO is also a grassroots project organised through a community network between Athens and eleven camps and community centres in mainland Greece.

Although ECHO is not a public library in a traditional sense, they are an excellent example of providing a safe and accessible space for learning and exchange to the most vulnerable individuals and communities housed in refugees camps in Europe. We interviewed full-time coordinators Keira and Becka from ECHO on what inspired them to start the mobile library.

Keira and Becka explained that once the EU Turkey deal was passed in 2015, allowing for refugees and migrants to move through Greece to get to the rest of Europe. This led to many informal camps springing up in the North of Greece, near the border region, including one in a disused petrol station called EKO. It was there that they saw a lot of solidarians who were helping out with people who are living in the abandoned petrol station. And a group of these solidarians (four of them) decided to start the library in that camp. Laura Samira Naude and Esther ten Zijthoff are part of this group who founded ECHO.

Their thinking behind founding ECHO was that people had many basic needs that weren’t being met in this informal camp, where there was also a desire and need for a shared space for people who could come together and talk and share their time. There was also a massive desire for education, continuing their lives and using the time that they’ve got to learn more and improve skills. Due to a lot of people who have their education journeys interrupted as they were moving through Greece.

There was also a desire for culture, literature and the arts and ways to experience the world and share art forms. That is why the founders of ECHO thought the mobile library is a brilliant way of providing these three things of facilitating those types of experiences and interaction through the medium of literature.

ECHO’s adaptation to COVID-19

In Greece, education substance was stopped in March 2020, which meant that no substances like the library could continue in real life, so ECHO had to shut down legally. This was quickly followed by a very strict lockdown that was introduced nationally. Keria defined how ECHO adapted to the pandemic once constraints were placed upon the way their library was operating.

“During this time, we sent out resources online to our database of contacts for our library users. We would text people in the relevant languages and inform them about what was happening and let them know they could access the resources line. So essentially, we had an online library in which people would text us to request a book, and we could send them the PDF of the book that we have.

The most significant things during the lockdown were that we are in a relationship with a broader grassroots solidarity movement in Athens. One of those groups was the Core Kitchen; usually, they have a restaurant, a free restaurant space where people can come and get quite nutritious food for free, in a safe space. They quickly transformed this into hot food distribution, like food deliveries, to people who are stuck without food during a lockdown. This was extended to groceries as well. The mobile library then became a food delivery vehicle, which occasionally doubled as a library van when people saw what was inside, which was nice. We ended up reaching out to people who’ve never seen the library before, and we deliver the food. Then volunteers in the kitchen helping prepare the food, and even people who were coming to get the food, or we were providing food to, would say, ‘ah, so what’s this? A library?’ So we also lent a few books that way. It didn’t put a total end to our book lending.

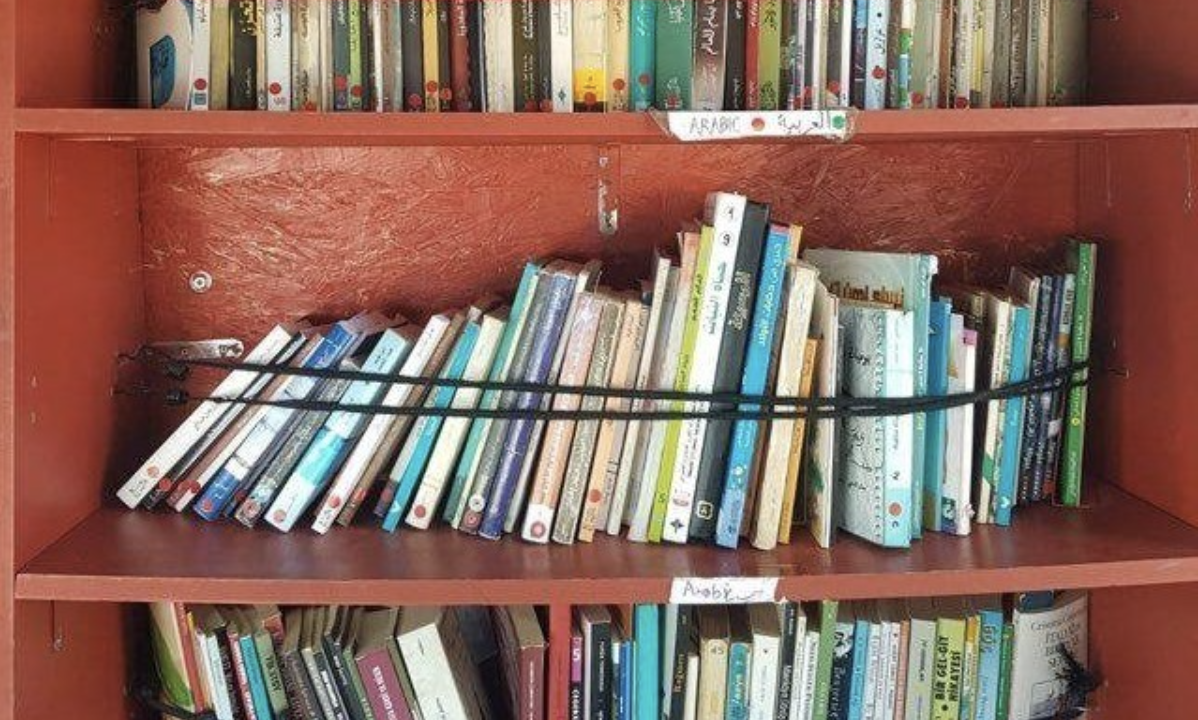

One of the young men from the Syrian Greek youth forum said, ‘are those books?’ ‘Are those books in Arabic? Can I have one?’ Most people don’t believe it. They think, ‘Oh, it’s a library. It’s probably a language I don’t understand.’ And then, as we were loading the hot food into the back of the van, they say, ‘wait a minute. Are those novels in Arabic!’ So we ended up lending English learning resources, distributing and giving away and lending out many Arabic novels.”

Sustaining solidarity between the individuals and communities across differences and borders and nationalities

When it comes to how ECHO fuels solidarity between individuals and communities, across differences, borders and nationalities, Keira describes that, “We often have many enthusiastic residents who come in and essentially help us run our library sessions every week, either on a particular day or in a specific camp. This has been great to see because we feel that you can empower those people to gain new skills and run something that benefits them and the camp’s fellow residents or wherever we’re working.

You can also see that in providing the only neutral space in an exceptionally linguistically and culturally diverse camp where resources are very few, and misunderstandings happen a lot of the time where things aren’t explained to you, and you’re treated like a number. We can provide this neutral space where we treat everyone as a person and try to say, ‘okay, what’s your request? What are you looking for? How can we help you? Yeah, we can try and find that book. Yes. I can try and find Swedish from Arabic.’ That can be a really lovely thing to see in action. Sometimes, we get Farsi speakers asking if I have books to teach, learn, self-study Arabic to Farsi, which I did, or the other way around. ‘Oh, do you have anything for me to learn Farsi through? So I can talk to my neighbours.’ This is encouraging to see.

We also try and encourage inter-communal friendships through our children’s sessions. This is where many of our volunteers were giving the sessions in simple English, something that is a real equaliser for many children. And it has been playing together, doing activities together. And you can see how quickly they pick up each other’s language, or they at least understand English or sometimes Greek, as well as a shared language to build friendships across what would often be a barrier that you cannot transcend.

In terms of building solidarity as a community, there’s the library’s aspect as a shared public space. There’s the sense that the libraries are shared for the facility or public space; that is neutral. We explained in a camp context that it could be divisive and difficult to participate in a shared public with both adults and the kids. However, with libraries, we can do so.

Then, there’s building solidarity amongst the team, which is made up of many different people from a lot of other places and having collective decision-making processes and just being together. And we try and do a little meal or an activity together once a month. That sense of working together as equals towards a shared goal amongst the teamwork, people are from loads of different places and backgrounds, and displacement experiences are another vital part of that solidarity, as is the broader community we work within Athens.”