Courageous Citizens: Sana Murrani

14 Aug 2019

In a series of interviews with grantees of our 2018 Courageous Citizens call, we start with Sana Murrani. She applied with her project proposal “Creative Recovery: Mapping Refugees’ Memories of Home as Heritage”. Now that the exhibition is over we asked her to share some thoughts with you.

Firstly, what was your idea about?

Creative Recovery was born out of a personal struggle and sheer intellectual interest I had with questions like: Where is home? What is home to you? And, Where are you from? All of which are questions I have been asked over the last 16 years as an immigrant here in the UK. Some people are just curious and others are interested in my background, my culture, while a few may have had ulterior motives. These questions were amplified not just for me but for all those who have crossed the borders into Europe from the Middle East and Africa in recent years. I felt I had to do something. Something that will allow them to answer these questions not just with words but with maps, photographs and collages too. Creative Recovery shows the narrative that the media misses from war-torn countries and others suffering from conflict. A narrative that is visually representing cultures and people from across the world and how they wish to represent their homes and homelands.

Did your participation in the incubator workshop help you transform your idea into an effective project?

Making me think about impact and ways of measuring that impact were the highlight of the incubator workshop. This is particularly enabled by discussions with other ECF grantees but most importantly with ECF team as they have a clearer overview of the type of impact that is fit for projects of the likes of mine.

What difficulties did you encounter in realizing the first steps of your project? And how did you overcome those?

The main difficulty, which was an issue throughout the life of the project, was the precarious and volatile lives that my project participants were witnessing. These are refugees and asylum seekers in different stages of their legal processes. We had to work around their court hearings, their lawyers’ appointments, and with a couple their deportation cases. Even though the project wasn’t designed to intervene in such processes, I felt as a fellow human, I had to write letters to lawyers and speak to local MPs as well as of course, working around these important events in people’s lives to re-schedule workshops and meetings. The other difficulty was the emotional and mental investment that I found myself facing especially as I got to know well each difficult story for each of the 12 participants. It was hard to detach myself from their daily struggles with the UK immigration system and housing needs. But I sought support from a social worker/psychology colleague who has worked extensively with people with vulnerable situations. That helped a lot.

As in all projects, small moments of “glory” confirm you in your belief you are doing the right thing. Can you describe one of these successful moments? What did it teach you for later steps in your project?

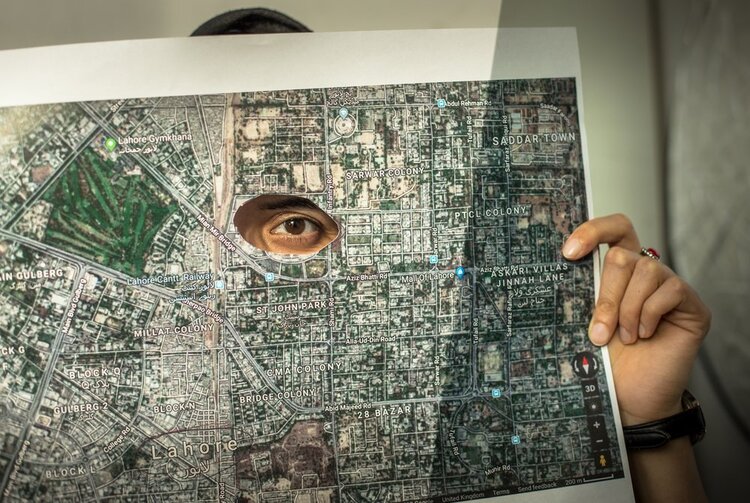

It was, without doubt, the moment when one of the participants, Mohammed from Gaza, made the first finding in the project as he was tracing his footsteps onto a map of Gaza where he realised the map wasn’t correct. We then looked at four different Open Source maps and overlayed them on top of each other and discovered that none of these maps are identical nor, according to Mohammed, correct. We then researched this particular phenomenon and discovered that for political and security reasons you will not find an ‘accurate’ map of Gaza anywhere. This was sad to discover yet certainly a moment of ‘glory’ as I felt that it wasn’t me (the researcher) but rather the participant who discovered this important point. That moment confirmed the participatory nature of the project where participants and researchers had equal roles and say in establishing the work and highlighting the findings.

What was the biggest surprise you did encounter in the project?

The stark difference between the current state of housing provided for asylum seekers and refugees in the UK and the previous lives and homes from which people have originated, was one of the biggest issues we had to deal with in the project. Yet the most heart-warming thing (rather than a surprise) was the resilience that all 12 participants had despite their current living conditions.

I suppose the biggest surprise was to see refugees and asylum seekers from different backgrounds put in shared housing across cities – and while the UK expects them to integrate within the British society without meaningful steps to explain how to integrate and what integration means, they are also lacking meaningful measures to help them understand each other’s cultures – yet they are expected to get along. For example, one of our participants lived in a house where five people from different parts of the world are supposed to share happily, a microcosm of multiculturalism, a house that is loaded with cultural differences, language barriers and different believes. This was one of the hardest facts to bare.

Did you achieve what you dreamt of? What impact did you generate?

It is more than I imagined. I gained 12 new friends! The project has been successful in the message it wanted to deliver. The final exhibition during UK Refugee Week was the highlight. People came from up and down the country to see it. The exhibition allowed the 12 protagonist a platform to speak and show their culture, their backgrounds and how they lived their lives in their homelands. What I hadn’t anticipated though was the interest of mental and community health specialists in the project. They found the methods of research used throughout the project to be empowering and are highly effective in art therapy context and recovery from trauma. I also found that the 12 participants have grown in their aspirations for success and change within their communities. A few have taken up initiatives alongside charities to support minorities and help them integrate within British society. This is besides the media interest. A BBC Spotlight story was dedicated for the project which appeared in full on TV and then a local Radio channel followed that. We also had gathered feedback from the exhibition which was overwhelmingly supportive and positive.

Do you see further development of your project in the future?

Yes in the form of extending the method established in this project for a further participatory action research project on local people’s history of loss and trauma after World War II. The South West of the UK had seen great damage to its cities’ infrastructure and housing stock during the war but also current austerity times are proving to be difficult for many (not the few), a project that will connect people with their past to help them see their current times and future especially as each city is becoming a multi/transcultural hub, would bring a better understanding of integration and community spirit.

More information via the project website and twitter feed.