Civitates: grantee stories

28 Feb 2019

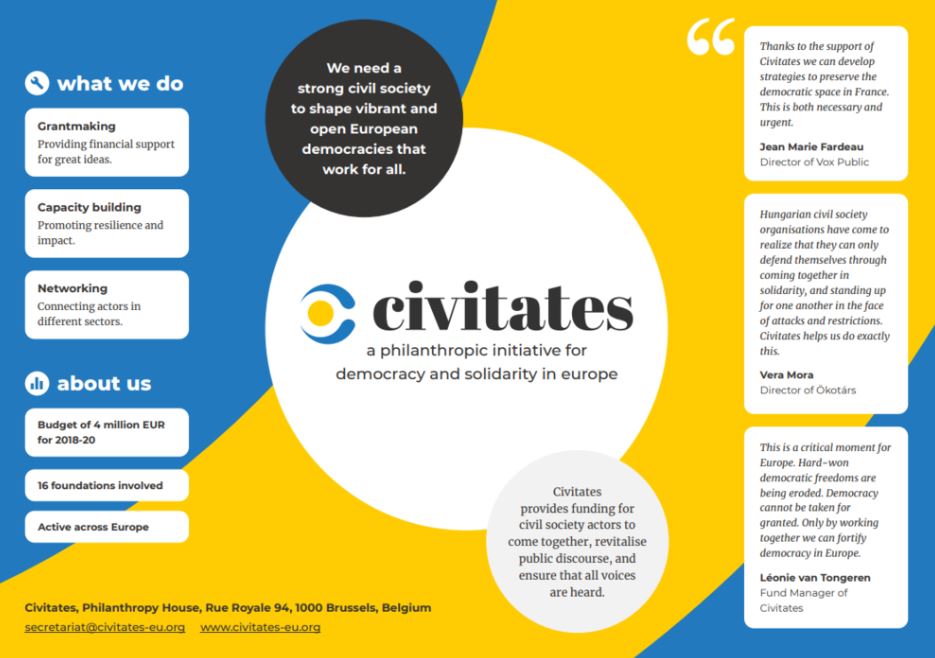

Earlier on we reported on Civitates – a funds pulled together by sixteen philanthropic foundations committed to protect and expand civil society at a time when the fundamentals of democracy are being challenged like never before. Civitates focuses on two vulnerable areas: the shrinking space for civil society, and public discourse and digitization. The work of two of their grantees shows the width of Civitates scope:

“We believe we are now stronger in the face of attacks and we will continue to build solidarity and trust in society.”

Dorota Setniewska from the NGO Klon/Jawor Association, a leading partner in a new set up aimed at boosting the profile and presence of civil society organizations in Poland, explains what is happening in the country and what has changed in recent years.

“At the beginning of 2017 we built an NGO coalition after a series of attacks against organizations on public television,” says Setniewska. The idea was not to focus on one issue, but to broaden efforts, engage with a variety of people and promote democracy across Poland. There are now over 30 organizations focusing on a range of issues whose work is boosted by the coalition.

Civil society organizations

Before we did anything, we wanted to make sure that the work of NGOs was in line with the needs of the country and that people understood the positive contribution of civil society organizations, says Setniewska. “We decided to check what people had in mind and what they expected from us,” she explains. “We created focus groups in different villages and cities across Poland.” From these meetings, the organizations understood that people often did not understand what was meant by terms such as “NGO” or “nonprofit”. For the general public, the term “social organization” was clearer and less abstract, says Setniewska. Using this term “brings us closer to people”, she believes.

Positive impact

“The public’s trust in polish NGOs is pretty high, but when we checked we found that people associated the civil sector with helping children or working on health issues, but not with democracy or civic rights for example,” says Setniewska.

The NGOs decided to change this by working more closely with people and showing the positive impact they are having in local neighborhoods. This led to the launch of a nationwide campaign called “Organizacje społeczne.To Działa” or “Civic organizations. It Works” in English, recruiting organizations from all over Poland and targeting different audiences to ensure the voice of NGOs is better heard in public debates and their work given more support and recognition. The campaign is being supported by consultants to improve the way NGOs in Poland communicate and strategize, not simply as individuals, but also together as a sector.

Joint calendar

“We are using social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube, and working with traditional media to tell emotional human stories, share infographics and use facts to bust myths,” explains Setniewska. The campaign is also aimed at encouraging members of the public to join civil society organizations or to carry out voluntary work with them.

The whole of the NGO sector has come together to work under the same umbrella to increase its impact and understanding of civil society organizations, she adds. This is helped by the creation of a joint calendar, enabling NGOs working on different issues to communicate with a single voice around a specific event or a special national or international day, such as the United Nations backed human rights or earth day.

Solidarity & trust

The impact of the change of direction so far is pretty difficult to measure, admits Setniewska, but she insists the NGO coalition will continue to measure reactions and coverage in the media. It may even hold new focus group meetings in the future to see whether public perception has altered. Most importantly is that “we are in this for the long haul”, she says, estimating the campaign will need to continue for ten years or longer to really make a difference in the fight against civic space shrinking in Poland. “We believe we are now stronger in the face of attacks and we will continue to build solidarity and trust in society,” says Setniewska.

“We need to think differently, use new messages and voices.”

Andrea Menapace from the Italian Coalition for Civil Liberties and Rights explains why it is vital to boost NGO communication on migration to the “undecided and persuadable middle”. “The political climate is more divisive than ever,” says Menapace, whose organization leads a coalition of NGOs pushing for change. Mainstream journalists and newspapers have been directly attacked for criticizing the government’s policies on migration and there has been a rise in racist and xenophobic violence in Italy.

Yet, among the doom and gloom, there is a hope, he insists, citing a study on national identity, refugees and migrants that shows Italians fall into seven different groups on the issue. Twenty-four per cent reveal themselves to be hostile to open society values, 28% can be considered allies of NGOs, while 48% are part of a silent, anxious and undecided “middle”. It is this group the coalition plans to target with its communications campaign.

Narrative change

More concretely, this means working on a broader mandate of defending the rule of law and the fundamental principles of an open society, rather than focusing just on migration, explains Menapace. “Civic space is something that matters for everyone.”

To achieve this, the NGOs are working on “narrative change and building a coalition to examine how we talk about the problem of migration and refugees,” he says. “More and more it is not a debate about the people who are coming to Europe, but about who we are as a society,” adds Menapace. “Italy has always been seen as a country from which people emigrated, not one to which people migrated. This has changed dramatically.”

Menapace and his colleagues want Italy and its people to debate these issues with facts and stop the civil space being overtaken by the toxic, xenophobic rhetoric of certain politicians. They are creating a positive core narrative that they will use to engage with a wide variety of groups, including trade unions, young people and religious organizations, and will examine how best to communicate with each group.

“NGOs generally have little communications capacity and tend to give messages based on their own values,” says Menapace. “We need to think differently, use new messages and voices.” He cites young business leaders or sports stars who originally arrived in Italy as migrants themselves as potential new voices to lead this debate.

Capacity building

To enable civil society organizations to make the most of this change of direction, the emphasis will be on capacity building and opportunities to experiment with different ways of communicating with new audiences. This will include a series of strategic trainings and workshops to generate a deep analysis of the current political situation, with a focus on common values and developing a shared language.

And it is important for the NGOs to ensure that the group they are ultimately trying to help is at the heart of the campaign. It will therefore include a mentoring program focused on migrants and second-generation immigrants and other unrepresented or misrepresented groups. The plan is to develop a series of training activities to help them become effective messengers, provide them with opportunities to spread their thoughts and ideas, and to create a community of practice, peer-to-peer learning and exchange between these groups.

There are unlikely to be any quick wins and changing the narrative and opinions in the middle ground will take lots of time and energy. But Menapace is optimistic that the NGO campaign will make a real difference, not just terms of discussions around migration and other minorities, but to stop civic space shrinking in Italy and opening up new conversations and ways of thinking.